Chenango Plantation

Brazosport Archaeological Society

Photograph Courtesy of Brazoria County Historical Museum Library 1936

Benjamin Fort Smith moved to Brazoria County, Texas from Mississippi in 1832 and bought two tracts of land in the William Harris League east of Oyster Creek comprising ~1300 acres. Producing corn and cotton using African slaves he smuggled from Cuba he established Point Pleasant Plantation. The plantation became a way station for African slaves illegally brought from Cuba by the notorious slave smuggler Monroe Edwards who owned the plantation for a short period changing the name to Chenango according to tradition[1] In 1839 while living in Galveston, Texas James Love, noted jurist and partisan politician, acquired the property, which had grown to ~3400 acres in the William Harris, Joshua Abbott, and Stephen Richardson Leagues through the transactions of several previous owners. He and his co-investor, Albert T. Burnley of New Orleans, ran the plantation in absentia until 1852 when William H. Sharpe of Louisiana acquired Love’s interest having bought Burnley’s share in 1850. James Love financed and built the first sugar mill on the property 1849-1852 while William Sharpe improved the mill by adding steam power. With a slave labor force Chenango Plantation was a consistent producer of sugar during the 1850’s. Sharpe developed a partnership with William J. Kyle and Benjamin F. Terry of Fort Bend County while he and his family managed Chenango through the Civil War. A mortgage foreclosure forced a public auction of the property to Henry H. Williams and John L. Darragh of Galveston in 1869. William Sharpe and his son Henry, member of Terry’s Texas Rangers during the Civil War, stayed on the plantation as managers for Darragh using tenant farmers who shared in the crops. By 1881 the Williams heirs assumed total control and in 1884 sold the property to A. C. Barnes. The 1900 hurricane leveled most of the structures on the property. Various groups and land developers have purchased the property over the years. The sugar mill, the only remaining remnant of Chenango Plantation, lies in a state of ruin.

William Harris of Maine received from the Mexican Government the grant for his league of land on the east side of the Brazos River along Oyster Creek July 10, 1824. The 1826 Census of Austin’s Colony listed him as a farmer and stock raiser aged between twenty five and forty. He had a wife, Ruth [2], one son and a daughter. While he was in Brazoria County in the middle 1830’s he did not settle on his league of land. Early on he sold several tracts from the league.

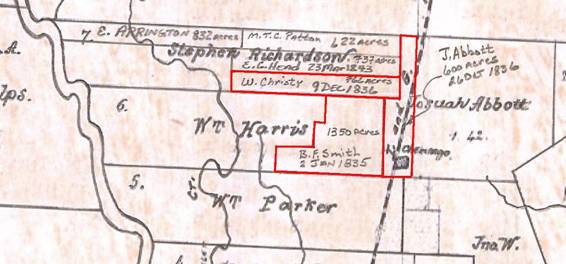

Texas General Land Office 1879

(Chenango Station on the International & Great Northern Railway is not Chenango Plantation)

Benjamin Fort Smith [3] of Hinds County Mississippi moved to Texas in late 1832 and became a citizen in 1833. Benjamin F. Smith acquired ~600 acres previous to 1835 and January 1835 he bought another 781 acres south of his original tract from Jared E. Groce [Brazoria County Deed Record [4] C: 207/08]. Benjamin F. Smith would make this ~1300 acres his home, Point Pleasant Plantation.

Eastern Portion of the William Harris League, Abstract 71

His sister Sarah David [5] married Joseph R. Terry in Kentucky April 17, 1816. Sarah and Joseph Terry reportedly separated about 1833 because of Joseph’s insistence on running a gambling house in Jackson, Mississippi. She accepted her brother, Benjamin’s proposal to bring her children, move to Texas and reside on his plantation.

In the winter of 1833-34 Benjamin F. Smith made a trip to Cuba to procure African slaves to work his lands. Though the importation of slaves from Africa was illegal, his vessel landed at Edwards’ Point on Galveston Bay. While making his way from Galveston Bay to his plantation Smith became lost and approached the home of Dr. Pleasant W. Rose ~25miles north of his home:

February, 1834

One cold day we could see in the direction of Galveston Bay a large crowd of people. They were coming to our house…When they got near our house there were three white men and a large gang of negroes. One man came in and introduced himself as Ben Fort Smith. He said he lived near Major Bingham’s, and that he was lost and nearly starved. He asked father to let him have two beeves and some bread…One man made a fire near some trees, away from the house. As soon as the beeves were skinned the negroes acted like dogs, they were so hungry. With the help of father and uncle, the white men kept them off till the meat was broiled, and then did not let them eat as much as they could eat. After dinner, Mr. Smith explained to father how he came to be lost on the prairie…The negroes were so enfeebled from close confinement that they could not travel. He rested one day, and would have reached home the next night if he had not got lost Uncle James guarded the negroes. They did not need watching, for after dark they went to sleep and did not wake till morning. They were so destitute of clothing, mother would not permit us children to go near them. Next day they cooked their meat before they began eating.

…After three or four days, he (Harvey Stafford) and Frank (Terry) [6] returned. Mr. Smith’s body servant, Mack, came with them and brought a wagon and team and clothing for the negroes. Mack made them go to the creek, bathe, and card their heads. After they were dressed, he marched them to the house for mother and us little girls to see…They did not understand a word of English. All the men and boys in the neighborhood came to see the wild Africans.

…He (Ben F. Smith) had a large scaffold built over a trench and made fire under it. He butchered the beeves and dried meat over the fire. After a few days he sent Frank Terry and Mack home with the negroes…[7]

During the revolution Benjamin F. Smith participated in hostilities at Gonzales and the siege of Bexar. In November 1835 he left Texas to recruit in Mississippi. Returning in March 1836 he reentered the army as a private and fought in Henry W. Karnes’ cavalry company at San Jacinto. August 1, 1836 he submitted his resignation to General Thomas Rusk which was accepted:

1 August 1836 Camp Coletto

… cannot permit this occasion to pass without expressing to you my entire approbation of your official conduct as well as of your Brave and Chivalrous bearing before the enemy on the plains of San Jacinto…

General Thomas J. Rusk [8]

September 1836 Monroe Edwards bought the plantation, 17 African slaves, and the cotton & corn crop for $35,000 from Benjamin F. Smith [BCDR A: 23/24]. Smith moved to Houston, where he built a hotel early in 1837 while his sister Sarah Terry and her children had previously moved north to a tract of land in the McFarland League to establish her plantation.

Monroe Edwards [9] was born in Danville, Kentucky. Financial reverses in Kentucky caused his father Amos Edwards to move his family to Redfish Bar, later Edwards Point, on the west side of Galveston Bay in ~1828-1830 [10. James Morgan visited Texas in 1830 [11]; he and his partner John Reed of New Orleans moved to Texas in 1831 and established a business at Anahuac on Galveston Bay [12]. Monroe’s clerkship with Morgan at Anahuac helped him learn the means to establish credit, and how to buy and sell cotton on consignment, talents that would later develop in the hands of a swindler. The Mexican authorities imprisoned him with William Barrett Travis, Patrick C. Jack, and others in 1832 at Fort Anahuac [13]. This disturbance led to the Battle of Velasco at the mouth of the Brazos River in June 1832 [14].

After the death of his father in 1832, the lucrative slave trade caught the attention of Monroe Edwards and in the spring of 1833 he and his partner Holcroft of New Orleans landed a shipment of African slaves at Edwards Point. At this time Edwards’ brother-in-law Ritson [15] Morris lived at Edwards Point. They had purchased 196 African slaves at $25 each and sold them for $600 each, realizing a profit of more than $100,000. The event was acknowledged by the Convention of 1833. The convention noted that a vessel had arrived in Galveston Bay, “direct from the island of Cuba laden with negroes recently from the African coast,” the convention resolved that, “we do hold in utter abhorrence all participation, whether direct or indirect, in the African Slave Trade; that we do concur the general indignation which has been manifested throughout the civilized world against that inhuman and unprincipled traffic; and we do therefore earnestly recommend to our constituents, the good people of Texas, that they will not only abstain from all concern in that abominable traffic, but that they will unite their efforts to prevent the evil from polluting our shores; and will aid and sustain the civil authorities in detecting and punishing any similar attempt for the future.” [16] Slaves could easily be purchased for $200 or less in Cuba and sold for $600-800 in Texas. Several “good” citizens of Brazoria County including General James Fannin [17], Sterling McNeel [18], and Benjamin Fort Smith along with Monroe Edwards continued to smuggle slaves into the county. A second cargo landed at Edwards Point in February 1834. This group of slaves was the same slaves previously mentioned owned by Benjamin F. Smith [19].

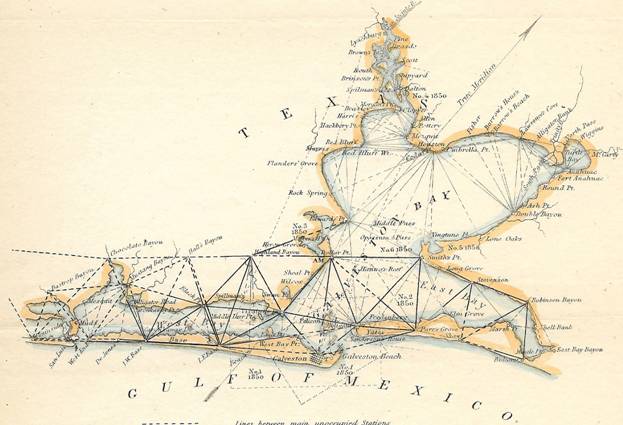

1848-1850 Coastal Survey Galveston Bay Author’s Collection

On March 2, 1836 the customs collector at Velasco, William S. Fisher, wrote Provisional Governor Smith:

The schooner Shenandoah entered this port on the 28th ult. and proceeded up the river, without reporting. I immediately pursued her… We overhauled the vessel that night, and found that the negroes had been landed –the negroes were, however, found during the night. The negroes I have given up to Mr. Edwards (the owner) on his giving bond and security to the amount of their value, to be held subject to the decision of the government. Sterling McNeal landed a cargo of negroes (Africans) on the coast . I endeavored to seize the vessel but was unsuccessful. This traffic in African Negroes is increasing daily…The number of negroes landed from the Shenandoah is 170[20]

The schooner Dart [21] sailed into Galveston Bay in March 1836 with 90 African slaves from Cuba. These were delivered to Ritson Morris, bringing to 122 the number of Negroes in his care. Shortly before the Battle of San Jacinto, at the approach of the Mexican army, the Texas war schooner Flash removed most of the slaves to Galveston Island. Two of these Africans were taken as far as Nacogdoches during this time as Morris advanced a claim to two Africans that had been held there, alleging that they, together with 120 more had been left in his charge by Monroe Edwards [22].

Monroe Edwards had slaves scattered from the San Bernard River to Galveston Bay. William Fairfax Gray traveling through Texas arrived at Mr. Earle’s home March 25, 1836 and noted:

…He has staying with him four young African Negroes, two males, two females. They were brought here from the West Indies by a Mr. Monroe Edwards. They are evidently native Africans, for they can speak not a word of English, French or Spanish. They look mild, gentle, docile, and have never been used to labor. They are delicately formed; the females in particular have straight, slender figures, and delicate arms and hands. They have the thick lips and negro features, and although understanding not a word of English, are quick of apprehension; have good ears, and repeat words that are spoken to them with remarkable accuracy…Their habits are beastly [23]. Captain Robert J. Calder, writing of his trek from San Jacinto battlefield to Galveston to notify the inhabitants that Santa Anna had been defeated noted:

The party reached the Edwards place at “Red Fish Bar” about noon of the third day. Here they found some provisions and a box of fine Havana cigars. The only living thing they saw was a wild African negro, probably one introduced by Monroe Edwards. [24].

William F. Gray visited the home of Edwards on Galveston Bay April 30, 1836:

…Ran into a cove near Clear Creek, and landed at the home of Mr. Edwards, where we found Ashmore Edwards and his brother-in- law, Ritson Morris (Jaw Bone M.), a Mr. Aldridge, and Mr. Stanley…Edwards is the nephew of Colonel Edwards of Nacogdoches, and the brother of Monroe Edwards, who imported the Guinea Negroes from Cuba about a month ago. About fifty of those poor wretches are now here, living out doors, like cattle. They are all young, the oldest not 25, the youngest, perhaps, not more than 10; boys and girls huddled together. They are diminutive, feeble, spare, squalid, nasty, and beastly in habits. Very few exhibit traits of intellect. None seem ever to have been accustomed to work…One girl sat apart and held no converse with the crowd. She is said to belong to a different tribe from any of the rest, and to stand her dignity. There is a boy also among them, about 14 or 15, a runt, who is acknowledged to be a prince, and deference is shown him. He claims the prerogative of five wives, and flogs them at his pleasure. They are mostly cheerful, sing and dance of [at] nights; wear caps and blankets; will not wear close clothes willingly; some go stark naked. A beef was killed at Morris’ home, 100 yards from Edwards’, and the Africans wrangle and fought for the garbage like dogs or vultures; they saved all the blood they could get, in gourds, and feed on it. An old American negro stood over the beef with a whip, and lashed them off like so many doge to prevent their pulling the raw meat to pieces. This is the nearest approach to cannibalism that I have ever seen.

Morris’ family have gone to the United States in the Koscuisko [25].

After the defeat of Santa Anna two groups of Monroe Edwards’ slaves and Ashmore Edwards returned via the schooner Koscuisko in an agreement with its captain James Spilman with 40 returned from the mouth of the Sabine and 54 from Point Bolivar. The $440 charged for the passage of the slaves and Ashmore Edwards from New Orleans would not be paid quickly by Monroe and would strain his relationship with James Morgan [26].

The slaves landed in February 1836 by Monroe Edwards had been funded in partnership with Christopher Dart of Natchez, Mississippi. In a suit George Knight & Co. vs. Monroe Edwards it was stipulated that “December 1835 money was advanced for the purpose of buying slaves in Cuba to be introduced into Texas and for the purchasing of Cannon for the Government of Texas the last of which cost five hundred dollars… The negroes left Cuba in the winter of 1835-36, and arrived in Texas before the second day of March 1836…The demand charged is admitted by the plaintiffs, and their fifteen hundred dollars were used by Edwards for his intentional benefit” [27]. In a deposition by John E. Sumner of New Orleans for the suit George Knight, Lambreto Fernandez and John Emilius Brylle [28] vs. Monroe Edwards it was stipulated that Edwards pledged he was to receive mortgage money from the firm of McKinney and Williams of Galveston for $500 per slave to pay the debt promptly and return to Cuba to purchase another group of slaves in a short period of time. Benjamin M. Steadman of Vickburg also gave a deposition stating that Edwards and Dart had arrived December 1835 in Havana with ~$50,000 in cash and financed the purchase of 188 slaves at $357 each for a total of $67,116. Additional funds were needed for aiding Monroe Edwards to purchase “Brass cannon, Gun Powder, Cannon Balls, a Jolly boat, fuel, Peas, Beans, Grain, Bananas Oranges…& in saving Monroe Edwards from prison…” [29] The slaves left Havana on the 17th and arrived the 28th of February. Having received Power of Attorney from Monroe Edwards May 16, 1836 in the city of Natchez, August 29, 1836 Christopher Dart signed a note for $35,410 with George Knight & Co. to cover the purchase of these slaves [30]. In return, Edwards signed ½ ownership of his property and Negroes in the Republic of Texas to Dart April 18, 1837 in New Orleans [31].

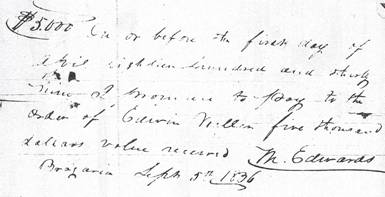

In September 1836 using funds from the sale of his African slaves as down payment, Monroe Edwards purchased the Chenango Plantation from B. F. Smith’s and on the same day he also purchased a plantation containing a quarter league on the San Bernard for $5000 from Edwin Waller.

[32]

[32]

The next day he purchased the Jesse Thompson League less 622 acres on the San Bernard from Columbus Patton for $20,000 [BCDR C: 75/76]. Several more tracts were bought in co-ownership with Peyton R. Splane in other counties in March 1837 [BCDR C: 164/67].

By this time Monroe Edwards was quite a figure in Brazoria County. November 1836 Mary Jane Harris was a passenger with her grandfather on the Julius Ceasar which landed at Quintana. Staying at a two story boarding house she peeped through a wide crack in the partition wall and watched Edwards as he sat at a table eating enormous quantities of baked sweet potatoes. She noted his rich and gaudy attire, his flashing diamonds, and his gaily caparisoned horse. [33] Edwards not only sold slaves but leased them out for terms. Peyton and Ann D. W. Splane contracted to split their cotton crop on “Gin Place” on the west bank of the Brazos River with Edwards furnishing 20 slaves, ½ the teams, and ½ all other expenses for the year 1837 [34].

At this time according to Brazoria County tax records for 1837 & 1838 Monroe Edwards owned:

4404 acres On Galveston Bay (His father’s league) $23,320

4000 acres On Bernardo (Jesse Thompson League) $20,000

1111 acres On Bernardo (Bought from Edwin Waller) $5,555

800 acres Cedar Lake $4,000

1600 acres On Brazos (Possible Chenango?) $8,000

92 Negroes $73,600

200 Head Cattle

8 Oxen

2 Horses

1 mule

Total value $139,500

Although Abner Strobel claimed: “He was kind and generous to his slaves, and they all thought kindly of him, and thought there was no one his equal…[35]” the record seems to prove the contrary. Monroe Edwards was indicted by a grand jury investigating thefts by slaves. The Negroes were not censured, but Edwards was accused of their maltreatment:

Republic of Texas District Court

County of Brazoria Spring Term 1838

We the Grand Jurors upon our oath present, that the Negroes of Monroe Edwards have for some time past been guilty of numerous thefts, in the neighborhood of Columbia, and that from circumstances within our knowledge we believe that they have been impelled to such conduct from want of sufficient food and such treatment as common humanity requires should be extended to slaves, we therefore present the subject taken in consideration of the court [36]

In December 1837, Monroe Edwards decided to make plans for a trip to Europe. While traveling Edwards would leave his brother Ashmore in charge of his business. Being a prominent and highly respected plantation owner, and a man with elevated standards, Monroe intended to see the continent first class.

Edwards would need a considerable amount of cash. In addition to the revenues generated by slave sales and leases he liquidated some of his land holdings by selling his interest in the Jesse Thompson League to William B. P. Gaines for $40,000 which was a nice profit in just over a year’s time. Additionally he sold him an undivided 15th in the town of San Bernardo [37] for $5000 cash. This town was to be located on the east bank of the San Bernard in the Jesse Thompson League [38]

As a preliminary to his voyage, he took a trip to Washington. There the minister of the Republic of Texas to the United States agreed to help him. The minister obtained letters from some of the most outstanding men in the country introducing Monroe Edwards to high statesmen and noblemen of England. Monroefelt the need of a military title to lend dignity and weight to his reputation. Upon arriving on the continent he would choose the title of Colonel and began portraying a hero of the Battle of San Jacinto for his interested new acquaintances.[39]

Before leaving, however, in New York City his past started to catch up to him for a while as he was accosted by J.P. Austin, a collector for the owners of the Koscuisko who Edwards had still neglected to pay. James Morgan had tried on several occasions to collect this debt and finally forwarded it to the owners of the vessel in New York. Monroe Edwards was irate with Morgan and wrote him an “insulting” letter from the Astor House in New York Cit, May 17, 1838. In Morgan’s reply he denied any “malice-envy-nor persecution” on his part but that this was “business” and that since Edwards had not tried to make payment it was out of his hands [40].

While Monroe Edwards was in Europe the note to George Knight & Co. had become due and Christopher Dart was left owing the note. He came to Texas and brought suit against Edwards and began to try to collect debts owed their partnership. On Edwards return he hired John C. Watrous, who had only recently retired as the Attorney General of the Republic of Texas and John W. Harris, outstanding Brazoria lawyer, to defend his claims.

Christopher Dart agreed to 5% on the amount of the judgment if satisfied in his favor to hire his attorneys William H. Jack, Patrick C. Jack, and Robert J. Townes using 10 slaves as collateral, August 18, 1838. Ten slaves were made part of a mortgage: Alfred (hired to F. W. Sawyer), Kitty (hired to Theodore Bennet) Prince, Juqua, Jock, Bob, Manola, Gasha, Ego and Charley.[41] The 1st of November Dart mortgaged all the slaves (91) that were in Edwards possession as well as turning over all the debts owed to Edwards to George Knight & Co. to secure his $35410 note.[42]

Public sympathy seemed to be on Monroe Edwards’ side. Those suspicious about Monroe remembered a court suit brought by Robert Peebles in June 2, 1837, concerning an African slave named Fagbo. Peebles, incredible as it seems, had bought a slave boy named Fagbo from Edwards for $1200, without having seen the boy. When Peebles’ overseer received the slave, he discovered that he was dying of pulmonary consumption and was unable to do any sort of work. Peebles charged that Fagbo had consumption at the time of the sale and was “afflicted with a disease in its nature incurable…that the slave has been valueless ever since the purchase and that in nursing and attending the slave” [43] he had incurred an additional expense of $100. Edwards had certified that the boy was in perfect health, and this certification of that condition was introduced in evidence in the trial. Dr. James B. Miller, who was called in to examine Fagbo, acknowledged that his illness was fatal. The court gave Peebles a judgment of $1,200 plus interest from the date of sale.[44]

By the 1839 tax records it was evident that most of Monroe Edwards’ assets had been liquidated or held separate. The record is listed under Dart & Edwards with 1107 acres of land, 97 Negroes, and 200 head of cattle for a total worth $76,235. [45]

At his trial March 1839 in Brazoria a bill of sale signed by Christopher Dart for his interest in the slaves and property was produced which was proved to be a forgery. A letter written by Christopher Dart had the body of the letter chemically removed and the bill of sale inserted with Dart’s original signature [46]. Edwards was indicted for the capital offense of forgery but was able to post bond and flee Texas with two of his young slaves, Kitty Clover and her brother Henry [47] Their description by another stated “They strongly resembled each other, both having the Congo mark on their cheeks (three perpendicular marks on each side of about two inches in length), they both were very dark, with strong negro features.” [48] Riding on horseback they proceeded by way of Nacogdoches before crossing into Louisiana [49]

In June 1839 James Treat in New York wrote to James Morgan including a passage about Edwards in his lengthy letter:

…You shall know all about Edwards suit, in my P S. It is not very improbable that he will get away from Jail. Jim Prentiss I have but little communion with and Willis Hall is now the Attorney General of the State and of course a very great man. I see but little of him now. I have apprised Henderson about this Edwards affair & c. and also Sam S. & Judge W. came to apprize me of Edwards arrest, and put me on my guard about writing to him & c. a pretty good joke indeed & Judge W. moreover told me he never like the man E. & ___ not be seen in the street with him even in Paris. A pretty fair story don’t you think so?—I told Gen Hamilton of it a week since in Phila He had not then heard of it…[50]

Upon arriving in Mississippi Edwards was arrested for the illegal introduction of the two slaves into the United States, and held to bail, and upon trial was fined $1500, which was subsequently remitted by President Van Buren. [51]

Christopher Dart won his civil suit, April 2, 1840 and was awarded $89,088 with 5% interest from April 1, 1840 subject to debts against and amounts due their partnership, Edwards would be enjoined from selling or conveying any of the property of said firm, and their partnership would be dissolved [52]. Dart would die before the transactions would be complete and his widow, Catherine B. would be made part of the judgment [53].

Reaching New Orleans Kitty was put aboard a ship to Liverpool England with two Spaniards with whom he had done business with on his last shipment of slaves. These men were to be witnesses concerning the slaves which had been smuggled into Texas [54]

May 1840 Monroe Edwards wrote from New Orleans to President Mirabeau Lamar pleading his innocence in the form of a veiled threat: …Said African negros were imposed on me as slaves for life, when in fact they are only apprentices for five years. I was not fully in possession of the facts …said negros are of that description known at Havana as (Amancipados) freed, being captured by a British man of war& brought in as a prize…The facts of the whole case have already been forwarded Her Majesty’s Ministers…I was the innocent instrument of bringing these Africans to Texas, and I am only doing my duty…[55] This letter and a similar one to Sam Houston imply that he might have been trying to use his slaves as a wedge between the Texas and English governments to possibly hinder the successful negotiations for the Texan loan which was currently being pursued by James Hamilton Envoy of the Republic of Texas.

Monroe Edwards and Henry traveled up the Mississippi to Cincinnati Ohio where he began negotiations with the abolitionist community. An article published in the local newspaper proclaimed that Monroe Edwards, Esq., of Iberville, Louisiana had emancipated 163 slaves at Cincinnati. Through this bogus article probably written by Edwards he was able to negotiate a loan and proceed to New York [56]

Writing several letters to Lewis Tappan, a noted abolitionist in New York state, Edwards attempted to raise cash for his trip to England [57]:

City Hotel, June 27, 1840

LEWIS TAPPAN, Esq.

…I this morning commenced a circumstantial narrationof all the facts connected with the 200 Africans now in Texas, upon whose liberation I am determined to hazard every thing. I this morning made an effort through a friend to raise ten per cent of its value upon some valuable real estate that I own in the city of Mobile, …suggested a plan which if it meets the approbation of the friends of universal emancipation here will enable me to visit England…The plan is to raise $5,000 on property in Mobile worth $50,000…I have been led to believe that there are gentlemen here who are zealous in the cause I have now embarked in…I expect their co-operation to enable me to carry out what to me is now the paramount object of my life…My unalterable determination now is to go to England and in person represent the facts of this peculiar case…[58]

Lewis Tappan, however, was very skeptical of Edwards’ claims and found the legal documents of Edwards recorded in Ohio emancipated only two slaves, one in New Orleans and the other in Cincinnati, Kitty and Henry. [59] Edwards, however, obtained another loan and proceeded to England 1st of November from Boston along with Henry and Col. J. S. Winfree (gambler). [60]

Arriving in London Edwards presented a letter of introduction from no less that Daniel Webster to Lord Earl Spencer. This letter obtained a loan of £250 which, of course, was not recovered:

Marshfield, Oct. 29th, 1840

My Lord,

I have taken the liberty to introduce to the honor of your acquaintance, my valued friend Col. M. Edwards, a highly respectable and wealthy planter of Louisiana, who visits England with the view of conferring with H.M. Gov’t. on the subject of 200 African captives, now illegally held as slaves in Texas…he with a magnanimity before unknown, attempted their restoration to freedom, by sending them to an English Colony, but was prevented from doing so by the direct interposition of the Gov’t. of Texas…

Any service it may be in your Lordship’s power to render Col. Edwards in promotion of his most praiseworthy object, will be properly appreciated…[61]

Lord Spencer wrote to Daniel Webster warning him of Edwards’s exploits and Webster published a letter warning the public:

…The accompanying letter, purporting to be written by me, is an entire forgery.

Of this Edwards I had some previous knowledge, as he attempted similar frauds, some time ago, upon the late President of the United States, and my predecessor in the Department of State….[62]

In London James Hamilton found it necessary to expose Edwards:

No. 15 Cockspur Street London November 23, 1840

Sir: I have just been informed by Mr. Stevenson that you have presented to him a letter of introduction, asking his good offices, from the secretary of state of the United States, and that you have a similar letter to General Cass, the American minister at Paris. I beg leave to inform you that I have apprized Mr. Stevenson that you are a fugitive from the public justice of Texas, charged with the commission of an infamous crime. I shall feel it my duty to make a similar communication to General Cass.

I likewise understand that you propose making an application to Lord Palmerston for the aid of her majesty’s government for the purpose of subserving some alleged objects of public justice in Texas . As the representative of the Republic of Texas in Britain, I shall not fail to advise Lord Palmerston of the facts which I have communicated to the representatives of the United States at Paris and London.

I hope you will spare me the pain and necessity of a more detailed and public statement of your recent history in Texas.

I remain your obedient servant,

J. Hamilton, Envoy of the Republic of Texas [63]

James Morgan heard from his friend Samuel Swartout shortly after, acknowledging that Monroe Edwards had left England and was headed to France:

London

31 March 1841

…I heard yesterday that Col Monroe Edwards had left England 6 or 8 weeks ago, after having borrowed about 500£ from his landlord at Long’s Hotel & then forged a receipt to his Bill of upwards of 100£ to impose upon others—With these outfits he made his way for France; it is reputed he has got into some similar scrape & is now in jail—But for God’s sake don’t say you hear this from me--Keep my name out of the question. Say if you speak of it that you recd the news by way of N. York—I dare say you’l have accounts of his conduct, as plenty as black [berries]…[64]

Monroe had left England putting Kitty, who was now pregnant [65], on a ship back to the east coast with Col. Winfree and Mary Moore (celebrated courtesan to put it nicely) while he went on to France.[66] Henry was put in school in England. As France also became too uncomfortable he joined them in New York. He and Kitty, who now had a child, moved to Philadelphia Pennsylvania Here he developed a most remarkable scheme of deception to defraud Brown Brothers & Co. and Fletcher Alexander & Co. of New York City for over $25,000 each. By forging letters of credit from Maunsell, White & Co. of New Orleans he established his new identity John P. Caldwell. Caldwell had more than one thousand bales of cotton worth at least fifty thousand dollars in the hands of Maunsell, White & Co., that any advance predicated on such cotton would be perfectly safe, he and his family were amongst the very few planters of Louisiana who were entirely free from debt, he was solvent and a very wealthy gentleman, and requested that if it would suit their convenience they had authorized him to draw on them for not more than thirty thousand dollars. This rues was perpetrated at both brokerage houses in August and September 1841. [67] After the fraud was discovered a $10,000 reward was posted by Edgar Corrie, Jr. and Brown, Brothers & Co.:

Whereas a person representing himself to be John P. Caldwell, has by means of forged letters of credit obtained upwards of $25,000 from each of the subscribers, notice is hereby given that the above reward will be paid on recovery of the money, or in proportion for any part of the same. [68]

As

the heat was on Monroe Edwards had an associate, Alexander Powell, who he tried

to pin the fraud upon by sending the authorities a letter identifying him as

someone of interest. Powell was to sail from

One of Colt’s revolving pistols 1 money belt

14 pair of pantaloons 1

pair of suspenders

1 bottle of hair dye 1 napkin

4 vests 1

bundle of type

3 coats 1

bundle of stamps

1 cloak 1

pair bullet moulds

1 blouse 1

box of cologne

1 stomach pump 1

powder box containing powder & bullets

1 book

The stamps were most

incriminating since one had “

16 shirts 1 stamp

16 handkerchiefs letters M. E.

1 pair of kid gloves 1

seal with coat of arms

1 blue sash 4

vests

1 bag gold

watch & chain

4 pair boots pair

of spectacles with blue glasses

Another item of interest was a

forged draft on Brown Brothers & Co. dated

Far

from

Monroe

Edwards was caught almost red handed but retained some of the most respected

lawyers on the east coast for his defense, U. S. Senator J. J. Crittenden and

Congressman Thomas F. Marshall[72] both of Kentucky among them. His trial

commenced on

As He Appeared at Trial in 1842 by Two Different Lithographers[74]

Most of Monroe Edwards’ defense stemmed from tampered hotel ledgers in cities on the same dates he was to have been instigating the fraud. A surprise deposition was given by Caroline Phillips, 18 years of age, who professed to be Edwards’ fiancée that he had a large quantity of cash in hand before the dates of the fraud. The prosecution had eye witnesses to Mr. Edwards and Mr. Caldwell being one in the same person, hand writing comparisons, and a clerk who actually marked one of the bags of money given to Mr. Caldwell. This bag was found in one of Edwards’ trunks. Another piece of evidence was the peculiarity in the spelling of the word “few”. In the forged letter signed Maunsell, White & Co. to Messrs. Brown Brothers & Co. this word is spelt “feu”. The same peculiarity was found in three letters written by Monroe Edwards to his friends. All of this in addition to the large amount of cash from an unknown origin.[75]

When Monroe Edwards had skipped out of Texas in 1839 he owed many but left Christopher Dart without title to the Chenango Plantation since his court suit froze Edwards’ assets as of April 18, 1837 [BCDR A: 96]. He had actually sold the plantation to Warren D. C. Hall[77] for $35,500 just days after he purchased it September 1836 [BCDR A: 96]. Warren D. C. Hall quickly sold the property to Vincent A. Drouillard for $40,000 the next month [BCDR A: 1/2]. September 16, 1837 Benjamin Fort Smith ran an advertisement in the Telegraph and Texas Register for the public sale of his previous property and African slaves indicating he had not been paid his latest installment of $18,000. Monroe Edwards’s true involvement with the original transaction became apparent as he included the following with the advertisement:

“As my name is necessarily used in the foregoing adv.,

and as the conclusion would naturally be that I am embarrassed or unable to pay

my debts, in explanation…I will remark that in the purchase of the above named

property I acted merely as the nominal purchaser of one Warren D. C. Hall; the personage

and the property itself being bound for the amount due thereon.

M. EDWARDS

Vincent

Drouillard purchased 600 acres just east of the plantation from Joshua Abbott

[BCDR A: 66/67] and shortly thereafter sold all his holdings to William Jarvis

Russell[78]

for $66,940 December 1836 [BCDR A: 68/70]. Russell added another 1200 acres

purchased from William Christy of

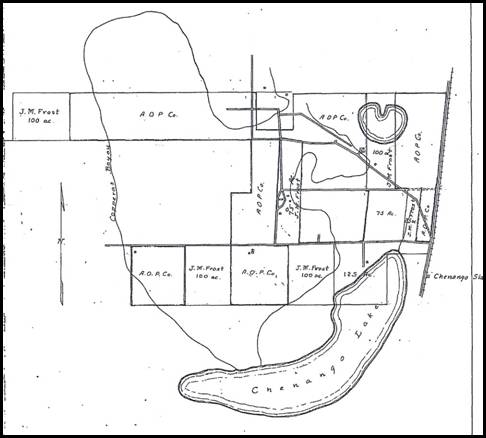

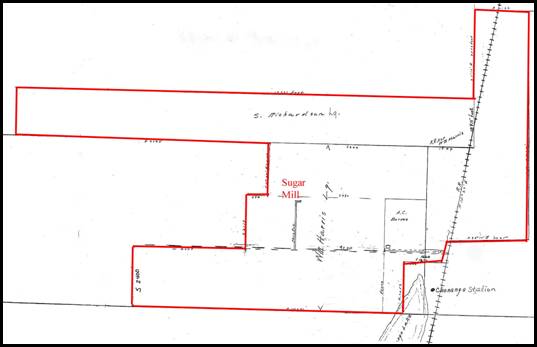

Tracts of Land Making Chenango Plantation

James

Love[79], jurist

and partisan politician, moved to

Tax

records indicate that by 1849 there were 74 slaves, 30 horses, and 1300 head of

cattle on the plantation. February 1849 James Love contracted with Rice, Adams

& Company[82] of

December

1850 Albert T. Burnley sold out his half share to William Sharpe of

In

April 1859 Samuel Green and Edward K. Harding sold their half interest to

Thomas W. Peirce of

William Sharpe 59 M

Eliza A. 45 F La. (Eliza Brown Avery Walsh m. 1854)

Henry 23 M

Robert Walsh 20 M

DudleyA. 18 M

Daniel H. 15 M

Mary 14 F

William 12 M

The slave census lists 19 slaves with 5 slave quarters. The 1860 Agricultural Census lists 600 acres improved and farm machinery valued at $800. He had 2 horses, 34 mules, 20 oxen, and 80 swine. His production was 3000 bushels of corn, 50 bales of cotton, 15 bushels of Irish potatoes, 300 of sweet potatoes, 150 pounds of butter, 8 tons of hay, 200 hogsheads of sugar, and 16,000 gallons of molasses.

Henry Sharp would serve with the Terry’s Texas Rangers during the Civil War. [86] Benjamin F. Terry who organized the regiment would die in their first skirmish. William J. Kyle would also die at home before the end of the war. The estates of both Kyle and Terry sought the division of the property to settle their affairs. August 1864 the lands and slaves were valuated with Sharpe taking the northern tract valued at $83,435 while the southern tract was valued at $54,125. After the division of slaves was complete it was established that Sharpe would owe the Kyle and Terry estates $13,750. December 11, 1866 Henry Sharp married Anna L. Turner.

By

1869 William Sharpe was again heavily in debt trying to make the Chenango

Plantation operational. He lost a judgment for $34,641.12 to Henry H. Williams

and $18,726.40 to John L Darragh of

Previous to the sale William Sharpe wrote John L. Darragh requesting the opportunity to lease or rent the property for the next few years:

Judge J. L. Darragh

I

am here in consequence of the ill health of my wife…I would like to rent the

Chenango Plantation for a term, say one, two, or three years, provided I can do

it in time, which would be by the first of October next so as to enable me to

lay away sufficient quantity of seed for the next year. It is all important to

plant a least one third of a cane crop annually…I find that I can certainly

procure labor, a thing, heretofore doubtful. Those hands on the plantation,

express a wish that I should remain, and declare their determination to leave

when I do…I take it for granted that you and Capt. H. H. Williams will buy the

plantation…[87]

John L. Darragh’s partner’s son John H. Williams was anxious to sell or the lease the property writing Darragh on several occasions making suggestions as to advertise for the rent or sale and letting know him know Alex Compton was interested “to rent the sugar plantation for 4 years at $1500 per year provided it is furnished with teams & utensils”.[88] The following advertisement appeared toward the end of the year:

FOR

A VALUABLE SUGAR AND COTTON

IN

The

Plantation formerly owned and cultivated by Kyle & Terry, and Sharp, known

as “Chenango,” situated as above, on the line of the Houston Tap and Brazoria

Railroad, containing about 1750 acres of land, 800 of which are in cultivation

and 250 acres in an excellent crop of cane, with all the best appliances and

machinery for making sugar and cotton, is offered for sale or lease, commencing

January 1, 1871, for the year or a longer period.

The

mules, horses, and utensils now employed in carrying on the plantation, which

was a good state of cultivation, also a supply of plant cane, can be had at a

fair price from the owners, the present lessees on the plantation. Ample timber

convenient. For terms apply to

J.

L. DARRAGH,

or

BALLINGER, JACK & MOTT

Evidently William Sharp was able to give them the best offer and his experience from having operated the plantation from 1848. One of the contracts for 1876 states that it is similar to their agreement in 1873 between John L. Darragh, John H. Williams and William H. Sharp with the following terms:

…shall each furnish 1/3 of all monies required for current expenses and

shall each be 1/3 interested in the proceeds of all crops & rents or

profits of the Plantation after deducting all expenses…the cultivation of the

Plantation …shall be under the Superintendance of W. H. Sharp …The said W. H.

Sharp shall receive $1000 in compensation of his services…The owners shall

receive a rent of $3000 payable out of the crop…The crop of cotton & sugar

shall all be shipped to the agents of the Plantation at Galveston & Houston & by them sold & the

net proceeds in their hands, shall be chargeable first with expenses incurred in

the conduct of the business during the year, next with salary of the

superintendent, then with the rent aforesaid payable to the owners of the

Plantation, after which the residue of the net proceeds if any shall be equally

divided between the parties of the contract…[89]

The 1876 expenses were $6542.77 while their total proceeds from crops was estimated to be $9219.07. J.L. Darragh’s share was estimated at $2792.22, J. H. Williams’ at $3687.16, and W. H. Sharp’s at $2739.69. The cash crops mainly consisted of 34 bales of cotton at $1331.26 and 55 hogsheads of sugar at $5497.16, and molasses sales of $1923.05. Fifteen workers shared in the cotton crop receiving $380.43 with some of them already receiving $123.40[90]

The year 1877 has some expenses listed for the sugar house maintenance giving an idea what part of the year different types of maintenance were being performed:

1877

Jan F.

Narbons act. for 1876 service as Machinist Boiler $10.00

Same

machinery

at S.H. $40.00

C. H. Thomas Black Smith grate puting in S.H. Windows

$16.25

Feb.

Brick $100.00

April

Hinges

for us of S.H. Mill Room $1.25

Work

at Gin House

$58.50

W. G. Mosely

Maps of

May

Cement

for S.H.

$29.25

FirebrickforS.H. $54.40

Shingles

& Sash for S.H. $52.65

June

Building

Cistern S.H.

$25.00

Cleaning

brick

$51.84

Aug

Pump

for Cistern

$19.95

Sept

Work

on boiler tubes

$19.10

Gin

& feeder

$16.40

October

taking flues from S.H. Boiler $20.00

Placing

new tubes S.H. $30.00

Nov

Copper

pipes for clarifiers $29.95

Pipes Pumps & c. $14.60

Hoses

for S.H. of ?

$29.50

3

pipes & fittings ? S.H.

$7.95

Lumber

& Shingles

$13.77

Nails

& c. $11.80

Material

for SH.

$50.30

Sundry

other Material S.H. $12.35[91]

Additional expenses listed over 591 cords of wood cut costing $441.35. Hogsheads, molasses barrels and kegs cost another $502.30. Wages paid for sugar making to C. S. Bennett and Charley Hawkins $120. Also listed is the payment of $600 to Captain Turner for his supertindance. The total expenses for 1877 approached $12,000 with half that being labor.[92] No list of crops produced was given.

William Sharpe and his wife moved back to Baton Rouge, Louisiana to the home of Samuel Walsh where he died in 1877 and his wife in 1884. His son Henry would stay on as manager for several more years not selling out their own personal property on the plantation until 1881. William also had part interest in a store in Chenango Station which was located just east on the International and Great Northern Railroad spur. He became Brazoria County Sheriff in 1879 and served until 1888. He died October 16, 1897 and was buried in the old graveyard in West Columbia with his wife and first son William.

1880 Census

William 44M Sheriff

Annie 37F

Andrew T. 10M son

Lou 8F daughter

Aileen 3F daughter

Katie B. 11mo. daughter

The Darragh family would sell their interest in 1881 to Rebecca A. Williams; and in 1884 she sold everything to A. C. Barnes for $10,500. In four years he was able to pay off his note and received clear title to ~3850 acres. Several owners and developers have owned the property since. The ruins of the sugar mill are the only structural remains from that era. The 1900 hurricane demolished most the structures that had remained until that time. Abner Strobel who was manager of the plantation stated: “Out of the 85 houses on the plantation in my charge, the next morning there were none habitable—practically all blown to splinters…”[93] Abner Strobel with his family lived in the second story of the sugar mill and had at least one daughter born there a week before the hurricane. He never owned a car and always rode in a buggy.

Mary and Lilly Barnard lived in the house as children in 1915 recalled:

“It was the oddest house,” says the younger

sister, Lilly. The first floor of the brick building was 16 steps up from the

ground girdled by a round verandah which was attached to three sides of the

house. On this level were two large rooms. From the rooms on the first level of

the house six more steps led to two rooms above. One of these was used as the

family’s living-dining room. From that floor was another flight of 21 steps on

the outside leading down to the ground in the rear of the house and to the

separate building which was the kitchen. There also was a second flight of six

steps which led directly to the verandah.

“It

was a fine modern kitchen,” claimed Mary Barnard, “I like it.” For 1915 it

probably was well equipped, with its built-in cabinets, wood-burning stove and

a sink with water piped in from the well.

Their

mother didn’t care for the inconvenience of going out in the weather to cook

and carry food up 21 steps to serve, so she had the stove moved up to the

living room and turned it into a kitchen, too. Water was brought from the

cistern on the verandah.

Each

of the four rooms had its own fireplace. Underneath the first floor of the

house was a storm cellar …

During

the War Between the States it was said to have been used as a prison for Yankee

prisoners. A smallpox epidemic broke out at that time, resulting in the death

of many prisoners and many of the slaves on the plantation. The Barnards say

they have seen a graveyard on the northeast end of the property where the

victims had been buried, but it was not marked, nor kept up, even at that time.

In

the early 1900’s Chenango was purchased by Dr. Harvey Motherell of Angleton.

The north side of the lake on the plantation was farmed by blacks, many

descendants of former slaves, while the southern part was farmed mainly by

German families. [The house at Chenango…Ill-fated as its first owner, Peggy

Case, The Brazosport Facts, Freeport,

Texas August 7, 1974]

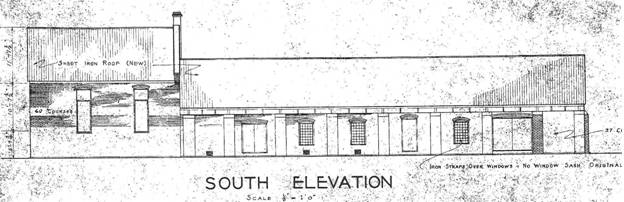

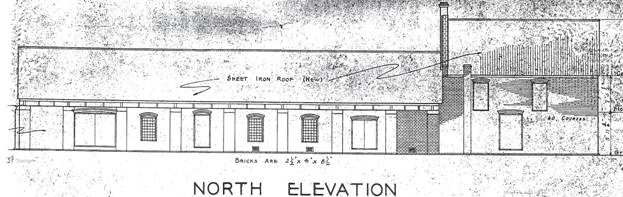

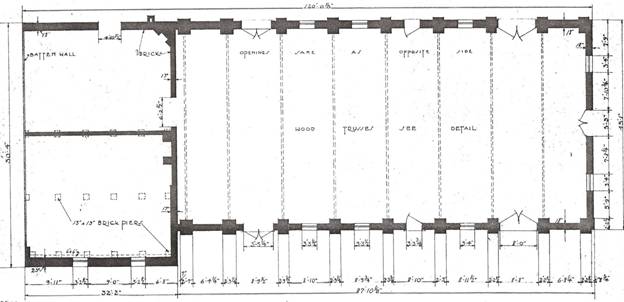

Several owners and developers have held the property during the past century. The property is now under development with the exact locations of the home site and slave quarters under question. The sugar mill is in a state of ruin with its roof falling in though many of the old mortise and tenon beams still remain. One underground cistern and a well are located west of the mill.

Chenango Plantation

~1920’s [

Chenango Sugar Mill

May 13, 1934

The Chenango remains after huricand Ike. These remains were leveled in 2014

West End of Chenango

Sugar Mill at time of Survey 2006

Appendix A

Bejamnin Fort Smith

to

|

Harry |

Tomy |

|

Cuggo |

Bancola |

|

Caro |

Peter |

Simon |

Itassi |

|

|

George |

William |

Juacco |

Anthony |

|

|

Dick |

Adeligna |

Daniel |

Eli |

All African |

Appendix B

James Love Mortgage Robert and D. G. Mills

|

Harry |

Adeligua |

Dick |

Yuoca |

Bob |

|

George |

Atalla |

Pete |

Tomy |

Ega and Child |

|

?lick |

Daniel |

Cojo |

Simon |

|

|

Bancola |

Willowee |

|

Tom |

|

|

Additional 8 women purchased by William Russell from

Monroe Edwards $7200 |

Tally |

|

2 Additional African Women |

|

|

Nancy & 2 Children |

Sally |

|

Charlotte & children |

|

|

Lucinda & 1 Child |

Clara |

|

Big Sally & children |

|

|

Alaba & 2 children |

Mary |

|

|

|

|

Jena & 1 child |

|

|

|

|

Appendix C

James Love Mortgage Nathaniel Ware

|

Harry |

Daniel |

Women |

Children |

|

Bancola |

Lewis |

Rose |

Eliza, Anthony |

|

Bob |

Jim |

Ega |

Opa, John, Frank, Jane Judy |

|

Addo |

Charles |

|

Caroline, Julia |

|

Ellich |

All Grown

Together |

Sally |

Malinda, Beshar |

|

George |

|

Fanny |

Tartor, Delta |

|

Itatio |

|

|

Gulens, Love |

|

Tony |

|

Malinda |

Mary, Martha, David |

|

Cudjo |

|

Lucinda |

Abbee, Henry |

|

Colo |

|

Sabine |

Polly, Caesar |

|

Dick |

|

Aliba |

LBill, Keto , Jack, Emiline |

|

Tom |

|

|

Louis, Martha, Jane |

|

Adelazua |

|

Muy |

Sam, Sally, Willowell grown |

Appendix D

James Love Mortgage William Rice & Charles W. Adams

|

Harry |

Yua |

Women |

Children |

|

Bancola |

Daniel |

Rose |

Eliza, Anthony |

|

Bob |

Lewis |

Ega |

Oscar, John, Frank, Jane Judy |

|

Addo |

Jim |

|

Caroline, Julan |

|

Ellick |

Charles |

Sally |

Malinda, Besha |

|

George |

All Grown

Together |

Fanny |

Lushe, Delta |

|

Italee |

|

|

Julius, Love |

|

Toney |

Original Africans |

Malinda |

Mary, Martha, David |

|

Cudjo |

Of |

Lucinda |

Abby, Henry |

|

Coca |

Ben F. Smith |

Sabine |

Polly, Carsai |

|

Dick |

|

Aliba |

Bill, Kits , Jack, Emiline |

|

Tom |

|

|

Louis, Martha, Jane |

|

Adela |

|

Mary |

Jane, Sally, Willowa grown |

Appendix E

William Sharpe to Green, Harding & Company

|

Name |

Age |

Name |

Age |

|

Ben Collie |

38 Yrs |

Isaac |

3 Mos. |

|

Lucinda |

36 |

Dilaper |

35 |

|

Delia |

5 |

Sallie |

33 |

|

Aleck |

35 |

Malinda |

11 |

|

|

33 |

Ann |

8 |

|

Louis |

15 |

Daniel |

35 |

|

Jane |

13 |

Malinda |

35 |

|

Martha |

12 |

Mary |

16 |

|

Martin |

7 |

Misson |

14 |

|

Clarissa |

5 |

Darcy |

12 |

|

Jesse |

3 |

Scippio |

10 |

|

|

8 |

Toby |

3 |

|

Peter |

4 |

Tom |

35 |

|

|

45 |

Rose |

33 |

|

Alaba |

35 |

Anthony |

11 |

|

Jack |

14 |

Simon |

8 |

|

Adelina |

10 |

Cudjoe |

40 |

|

Tanice |

6 |

Hyanea |

35 |

|

Teche |

3 |

Joe Cudjoe |

14 |

|

Addo |

45 |

Martha Ann |

10 |

|

Terese |

35 |

Big Lewis |

35 |

|

July |

16 |

Sabine |

32 |

|

Caroline |

13 |

Infant |

6 Mos. |

|

Sarah |

10 |

Eagel |

35 |

|

Emily |

2 |

Bob |

35 |

|

Dick |

35 |

Mary |

38 |

|

Little Sallie |

35 |

O Sue |

20 |

|

Joe Dick |

13 |

J. Burny |

1 |

|

Willie Ure |

50 |

John |

17 |

|

Nanny |

35 |

Frank |

15 |

|

Delta |

15 |

Judy |

9 |

|

|

35 |

Scippio |

7 |

|

Mary |

35 |

Big Jim |

35 |

|

Polly |

14 |

Sam |

16 |

|

Ceasar |

10 |

Abel |

7 |

|

Eliza |

8 |

|

|

Appendix F

1836 To Schooner Kusiosko & Owners

June To Ashmore

Edwards passage from

“ Mr. Monroe from Sabine “ “ “ 10.00

“ passage 40 Negroes from “ 250.00

“ “ 54 “ from Bolivar 150.00

and detention of vessel 2 days at

Point Bolivar

In Bringing

Boat from Sabine 10.00

$440.00

the Above Account is

Correct

James Spilman [James Morgan Papers 31-0376]

Appendix G

Chenango Plantation

By Marie Beth Jones[95]

(Printed in The Brazosport Facts 1960)

1947 1960 1960

He was a

Monroe Edwards was the sort of

man who inspired confidence in members of his own sex and fluttering hearts

among the ladies. From a refined and proud old

Edwards mingled with the wealth and

nobility of Europe, entertaining lavishly on the continent and telling

carefully modest—and entirely false—stories of his own heroism during the war

for

The Indian name of Chenango,

which he gave his plantation after a town in

A few hand sawn timbers from

that building have been preserved though the residence has long since been

destroyed by the elements. Two huge brick cisterns are buried underground at

that site.

Looking strangely out of place

in the modern Brazoria County Courthouse are crumbling, yellowed papers

inscribed in an almost illegible handwriting. They concern suits, trials and

land transfers in which Edwards was involved and form a large part of the early

court and deed records of this county. Still others are to be found in

Above all, there is the story of

a fabulous man who might have been a great power in developing early

Apprenticed to James Morgan,

Edwards’ life in

Though the Edwards family had

once been wealthy,

Morgan withstood the temptation

presented by those letters for two years before he and

Ashmore had moved to

Monroe Edwards has but one

favorable claim to recognition in history, and even that is open to some

criticism. He was one of 16 Texans who were imprisoned at

There were immediate reactions,

both for and against the actions at

One of

Whatever the wisdom of their

act, Edwards was for once in good company. Among those imprisoned with him were

William B. Travis, later to receive immortality at the

It was the following year

Edwards was seen by Mary Jane Harris of the family for whom

She noted his “rich and gaudy

attire, his flashing diamonds, and his gaily caparisoned horse.”

Another source mentions silver

trim on his saddle and bridle and his silver spurs.

A man of luxurious tastes, this

Monroe Edwards, and one who had no qualms about how he financed them. [The Facts,

Slave trading was a profitable

business back in 1833 if you had the stomach for it and were smart enough—or

lucky enough—not to get caught.

Monroe Edwards had met a man

named Holcroft in

All it required was a man with

the nerve to wink at the law and the cash to grease enough palms for the law to

wink back, Holcroft told Edwards. He would furnish the cash, Holcroft added

hastily. About that time Edwards became convinced that this was the opportunity

he had been waiting for.

Anxious to protect his

reputation and concerned at his family’s opinion should they know of his plans,

Edwards was cautious in broaching the subject to his mother. “I’ve been offered

an opportunity to engage in profitable business in

If Mrs. Edwards suspected

anything was wrong or had any doubts that

Edwards and Holcroft sailed from

The voyage brought with it many

complications and hardships, and at time Edwards must have wondered whether the

scheme was as clever as he had first thought. Finally, though, the hazardous

trip was finished, the slaves sold, and the profits were beyond Edwards’

wildest dreams.

They purchased 196 Africans at

an average price of $25 each and had sold them for about $600 each, realizing a

net profit of more than $100,000, of which, Edwards received on-half.

For that sort of profit, a man

could withstand a few inconveniences, could afford to take some chances,

Edwards decided. There is little doubt that he began then to make plans for the

future.

When he returned to his home, he

disclosed only the success of the business venture, not going into its methods.

His mother was elated at the news, heaping praise on

A large part of that money was

used to purchase a vast acreage in the rich bottom lands of northern

The family sold their place at

Red Fish Bar, and

He had established himself

firmly as a Southern planter in the months since that first smuggling trip, and

now he sought the advantages travel can bring.

He paid a lengthy visit to his

family in

Using the charm so many people

seemed to find irresistible,

According to law, slavery was

prohibited in

Reciprocal treaties between

The law required that after 10

years these slaves were to be liberated. A slave for 10 years was understandably, worth considerably less

than one required to serve his entire life. At the going rates, such

apprentices brought about $200 in

Edwards and Dart schemed to by

the slaves at

Edwards was in charge of the

Negroes during the trip from

Crowded into the hold of the

ship Shenandoah, the slaves moaned in terror at what would become of them. None

had found the 19-day journey from

The first load of slaves was

unloaded on

The date is one remembered by

Texans for another reason. On that same day, the Texas Declaration of

Independence was signed at

While his main occupation may

have had little to do with planting, Monroe Edwards gathered about him the

equipment and buildings necessary to that occupation including a fine sugar

house, its bricks hand made by slaves at Chenango Plantation, its double

kettles capable of processing quantities of the cane juice each season.

One historian describes Edwards

as being kind and generous to his slaves who “all thought kindly of him, and

thought there was on one his equal…to the last they revered his memory.”

Be that as it may, the Brazoria

County Grand Jury for the Spring Term , 1838, thought differently.

Some of his slaves were accused

of stealing two barrels of sugar and five sacks of corn, all valued at $106. As

their master, Edwards was held responsible and the charge of theft was lodged

against him.

In the indictment the Grand Jury

said, “The Negroes of Munro Edwards have for some time been guilty of numerous

thefts in the neighborhood of

The case was dismissed, but such

a charge leaves at least a little doubt as to Edwards’ kindness and generosity.

A peaceable man who had no

quarrel with the Mexican government—after all they had allowed him to make a

fortune on some pretty questionable transactions—Edwards decided he needed a

change of climate when the time came for Texans to fight for independence.

Leaving Chenango and his other

holdings for his brother, Ashmore, to care for, Monroe journeyed to

Not content to limit his social

accomplishments to any one place though, he traveled on to

On to

For some time

In a letter to Dart, he urged

that he should visit

Always the gentleman, Edwards

was on hand to meet his partner there, registering for the two of them at the

that city’s finest hotel, introducing Dart to the society and pleasures of the

fabulous city, and making plans to spend several days there rather than rush

immediately into business.

Hidden in the crowds on the

dock, another man took note of Dart’s arrival with a great deal of interest. It

was the gambler who bore such an uncanny resemblance to

Taking note of Dart’s attire,

his gestures, his manner of speaking, the gambler purchased clothing as nearly

as possible duplicating Dart’s. He then took his purchases to his room in

another hotel and began practicing in front of a mirror, waiting to be called

on stage by Monroe Edwards.

The resemblance was so great

that none of the people who had already met the Mississippian had any idea they

were now talking to someone else. As the imposter and Monroe chatted of

inconsequential matters to Captain Peyton R. Splane; recently a member of the

“Glad to do it,” that gentleman

replied, ”Always glad to be of service.”

Handing the documents to Captain

Splane,

The

The real Dart completed his

letter writing, and returned to

That was the clerk who had

stopped at Dart’s room on a minor errand and had noticed the gentleman had

taken off his shirt and was writing at a table. Returning immediately

downstairs, the man was almost sure he saw Dart talking fully clothed, with

Captain Splane and Edwards. For a few minutes he wondered about the oddity of

the situation and then dismissed it as of no importance.

After a visit of several days at

Chenango, Dart returned to Natchez, convinced his partner was a prince of a

fellow and an astute businessman, and that Chenango Plantation and its slaves

represented a fine investment. [The Facts

In January of 1838, Monroe

Edwards decided he had gathered enough moss in early

As a preliminary to his voyage,

he took a trip to

No matter that his last trip had

been taken mainly to evade service in the army of the

His introduction to the society

of

“He was not only a colonel but a

Edwards was entertained and

feted, taken to sites of interest, and introduced with a note of triumph. Over

and over he was asked to tell about

As the Gazette explained it,

“There was also the consoling thought that an opportunity would arise in the

course of things, to redeem the wounds of his purse through the same avenues by

which it had been drained. Keeping his eye always bent upon his chance of

replenishment, he continued his expensive course of life, supporting a

mistress, and sporting a tandem with the most ambitious bloods of the metropolis.”

He attended the coronation of

Queen

Though they hated to see him go,

his British friends agreed that a man must protect his interests and bade him

goodbye. One of the most prolonged and tearful of those farewells came from a

lady of quality with whom Edwards parted in

When he returned to

Ashmore was indignant at the

very thought of Dart’s duplicity, explaining that the property was under

sequestration and that Dart had accused

Monroe of attempting to defraud him of his interest in their partnership land

and slaves.

Edwards hired John C. Watrous,

who had only recently retired as the attorney general of the

Public sympathy seemed to be on

Those suspicions about

Edwards admitted selling the

slave to Peebles at a price of $1200. He had given Peebles a warranty that the

slave was sound, but Peebles charged that Fagbo had consumption at the time of

the sale and was “afflicted with a disease in its nature incurable…that the

slave has been valueless ever since the purchase and that in nursing and

attending the slave” he had incurred and additional expense of $100.

Peebles’ attorneys were William

and P.C. Jack, the latter on of

Though

Despite this caution, they found

it difficult to believe

In the days between Monroe Edwards’ return to

He was also prone to deep sighs for the English lady

he had been forced to leave, and began casing about for a handy substitute.

Before long he came to notice one of the slaves at Chenango, a beautiful and

seductive girl of 15 years who bore the appealing name of Kitty Clover.

Kitty was the illegitimate child

of a Spanish grandee in

“Her plump limbs being already

touched with a voluptuous finish that would have made her a fortune as a model

artiste, and had been gifted by nature with a Caucasian skin. As it was, her

pelt was but little darker than a golden brown…She had no blushes to suppress,

and her civil dependence left without condition to make or calculations to

consider. She gave nothing but what would become the windfall of some sooty

Tarquin, and in exchange she got ease, luxury and a celestial lover. Who could

blame her for the bargain?”

When the trial began, Brazoria

Countians crowded the courtroom to see Dart take the stand as first witness in

the case. Dart’s attorneys were the firm of Jack and Townes of Brazoria,

experienced and well known.

Their fee was to be five per

cent of the judgment or two and a half per cent of any compromise settlement.

As earnest money for that fee, Dart mortgaged 10 of the Chenango slaves to

them.

Edwards’ attorneys showed two

bills of sale bearing the signature Christopher Dart. One of them conveyed

Dart’s interest in the partnership lands, the others his half interest in the

slaves, to Edwards.

The signatures of Captain Peyton

R. Splane, John F. Pettus and Ashmore Edwards were inscribed on both bills of

sale as witnesses.

“Is that your signature?” the

attorney demanded.

With shaking hands, Dart

accepted the instrument from the attorney and looked at it long and hard. His

expression became stricken as he answered in a low voice, “I believe it is.” Horrified, his attorney said “Then

we abandon the case.”

“No,” said Dart quickly. “No. I

didn’t mean that I signed it. I never signed such an instrument as that. It’s a

forgery!”

A stir filled the crowded

courtroom as neighbors and friends of Monroe Edwards whispered and Judge

Benjamin C. Franklin had to ask for quiet.

Ashmore Edwards took the stand.

“Yes, I signed the instruments as witness,” he testified. “Dart was present

then and when Capt. Splane and Mr. Pettus signed them. I saw them sign in his

presence.”

His testimony carried the ring

of truth, for Ashmore Edwards believed it to be true. He as was as much fooled

by Monroe’s trick as everyone else had been and had not the slightest suspicion

that the man with Monroe when the witnesses signed those papers was a gambler

from Baton Rouge.

Sitting with his attorneys, Dart

had picked up the instruments and was examining them again. Suddenly he made a

small exclamation, and began to whisper to his counsel. Dramatically, the lawyers jumped to their feet, asking Judge

Franklin for a recess.

“Important evidence has come to

our attention,” they explained, approaching the bench. “We should like to have

time to plan our procedure in the light of this new evidence.”

They were careful to give

Edwards and his lawyers no indication as to what the discovery had been.

Actually Dart had recognized the paper used in the bills of sale as a special

foolscap he used only for letter writing. With that discovery came the

suspicion that the documents were actually letters from which all the writing

except the signature had been erased chemically, with bill of sale written

later.

There were two men in

Andrews was called to the stand.

Despite vigorous objects by Edwards’ attorneys, the court ruled that he could

apply certain chemical tests to the documents.

Conferring hurriedly with

Edwards his lawyers could do nothing to prevent the chemical tests after the

court had ruled. With a growing conviction that their case was lost, they

watched faint spidery lines, clearly distinct from the bill of sale become

apparent as Andrews applied his tests.

Dr. Stewart then took the stand,

agreeing with Andrews that there had been writing on the paper before the bill

of sale, and that the original writing had been removed by chemical means.

The situation looked bad for

Monroe Edward, but he had not hired the most famous lawyers in the Republic for

nothing. They were prepared to fight for their client.[The Facts,

Monroe Edwards had chosen his

attorney well. John C. Watrous, who had formerly been attorney general for the

“Your honor,” they said to Judge

Benjamin C. Franklin, “we ask in all fairness to Mr. Edwards if he should be

held responsible for any use Mr. Dart may have made of the paper before the

bills of sale were drawn?”

After all, they said, their

client had witnesses to the transaction. Ashmore Edwards had already testified

to signing the papers in

Despite the eloquent pleas of

Edwards’ attorneys, the jury returned a verdict against him. The partnership

property of Dart and Edwards was valued at $99,088. Judge Franklin, who

presided over the First District of the

Even worse things were in store

for Monroe Edwards. The following day, still smarting from the loss of this

suit, he and his brother Ashmore Edwards were arrested in Brazoria by County

Sheriff Robert J. Calder. Both were charged with forgery, and in

The news of this new development

traveled fast, and before long had reached even the ears of the 15-year-old

slave girl named Kitty Clover, whom

Without hesitation, Kitty Clover

made plans to help her master as best she could. She borrowed clothes from one

of the male slaves at Chenango and disguised herself as a boy, leaving Chenango

Plantation at

To the surprise of the jailer

there she announced, “I’m one of Massa Edwards’s boys. I’d like to see him. My

name is Henry Clover.”

Apparently without suspicion,

the jailer unlocked the door of Edwards’s cell to admit “Henry” and authorities

decided to allow Edwards to keep his slave with him as a personal servant.

Still working in behalf of their

client, Edwards’ attorneys journeyed to

The hearing was held within a

few days, Edwards traveling to

Edwards and his attorney John C.

Watrous decided to remain in

For

Reaching

This was the hotel clerk who had

seen Dart sitting shirtless in his room writing letters one minute, and

completely dressed, talking in the hotel lobby with Edwards and Captain Splane,

the next minute.

The clerk had long since put the

puzzling incident from his mind, but reports of the Dart-Edwards trial had

recalled it. Sure now that the man he had seen in the hotel lobby was an

imposter, the clerk’s testimony was sure to send Edwards to prison.

According to the plan she and

Edwards had made in San Antonio Kitty secured a horse and traveled to an inn

about 40 miles from Brazoria, where she waited for her master to arrive. Slipping a note to Edwards as he passed

through the stable, Kitty waited there until he had an opportunity to read the

message and come back outside. Without pausing he whispered that they would

leave at

Kitty had the horses saddled

when

They approached cautiously,

checking for any sign of activity that would mean authorities were waiting for

them. They stopped long enough to pack food and clothing and a bag of gold

Then they rode off toward the

southwest, leaving

Though Monroe Edwards had many

faults, lack of self-confidence was never one of them. Leaving Chenango

Plantation in

He told his mother a long sad

tale of how he had been persecuted, picked upon and robbed by trusted friends.

The story bore little resemblance to the truth, but he was always a convincing

liar.

After a short visit with his

family,

Looking up a wealthy planter he had known

earlier, Edwards was introduced to

He had the necessary papers

drawn up and by that time was held in high esteem by his abolitionist friends

that one of them was only too happy to cash a check for Edwards in the amount

of $2,000.

This meant a quick move to

Before the European voyage,

Edwards had written letters of inquiry on a host of different subjects to

several dignitaries and politicians. His

plan of receiving the replies bearing the signatures of such persons as Daniel

Webster, Martin Van Buren John Forsyth and others worked well. He then

proceeded to use his knowledge of chemical ink erasure to rid the paper of all

except the signatures, and to write in glowing introduction of Colonel Monroe

Edwards to high ranking British officials.

With these documents he and

“Henry” left for England, where Monroe hoped to cause all sorts of trouble

between England and the Republic of Texas over slaves which Monroe himself, had

smuggled some four years earlier.

He was convinced that this plot

would not only bring him respect and prestige in

It is indicative of Edwards’

supreme self confidence that he dared let his whereabouts be known to anyone of

importance in

In a letter to Texas President

Mirabeau B. Lamar, Edwards wrote from

Edwards explained that though

Dart had sold them to him representing them as slaves for life, they were

actually captured by a British man-of-war and brought to

Edwards gave the whole details

of the transaction—glossing over only his part in it—and advised Lamar that the

public should not purchase the Negroes since England would surely see to it

that they were released.

He was hoping his plan would

prove as profitable as the forged letters of introduction he was using in

General James Hamilton,

What he learned caused him to

write still another letter, this one to Edwards, informing him that the past

had caught up with him. “I hope you will spare me the pain and necessity of a

more detailed and public statement of your recent history in

Edwards made plans to leave as

soon as possible, but a voyage would take money. Therefore, he planned a last

touch to end his English social career. News of his past had preceded him,

however, and he was ordered from the office of Lord Brougham. That gentleman,

one of Edwards’ closest friends in

Forced by approaching motherhood

to resume the dress of a woman, Kitty Clover was sent back to the

Edwards had provided ample funds

for her to live well until he could join her, and had entrusted them to Winfree.

Edwards’ friends were not all honest, however, and Winfree kept the money for

himself.

Without funds, Kitty entered the

charity ward of

Kitty followed him in a short

time, and she and the child were installed with a Negro family there.

Despite the loyalty and devotion

she had always shown, it was Kitty’s presence in

Not the sort of person to gamble

for small stakes, Monroe Edwards assumed the name of John P. Caldwell during his operation in

In this way he obtained a loan

of $25,119.52, and when the financial geniuses found they had been led down the

garden path, they offered rewards totaling $25,000 for the apprehension of the

responsible parties.

On the day Powell’s boat was due

to sail, Monroe wrote an anonymous letter to the New York office of the bankers

from whom he had obtained the generous loan, suggesting that they might be

interested in Alexander Powell and listing the name of his boat.

He thought the boat would have

already sailed, and this would throw police well off his own track. To his

consternation, however, he learned that departure of Powell’s boat had delayed.

Quickly he sent a second anonymous letter to the bankers, cautioning them that

the first was a mistake and that Powell was actually a wealthy and influential